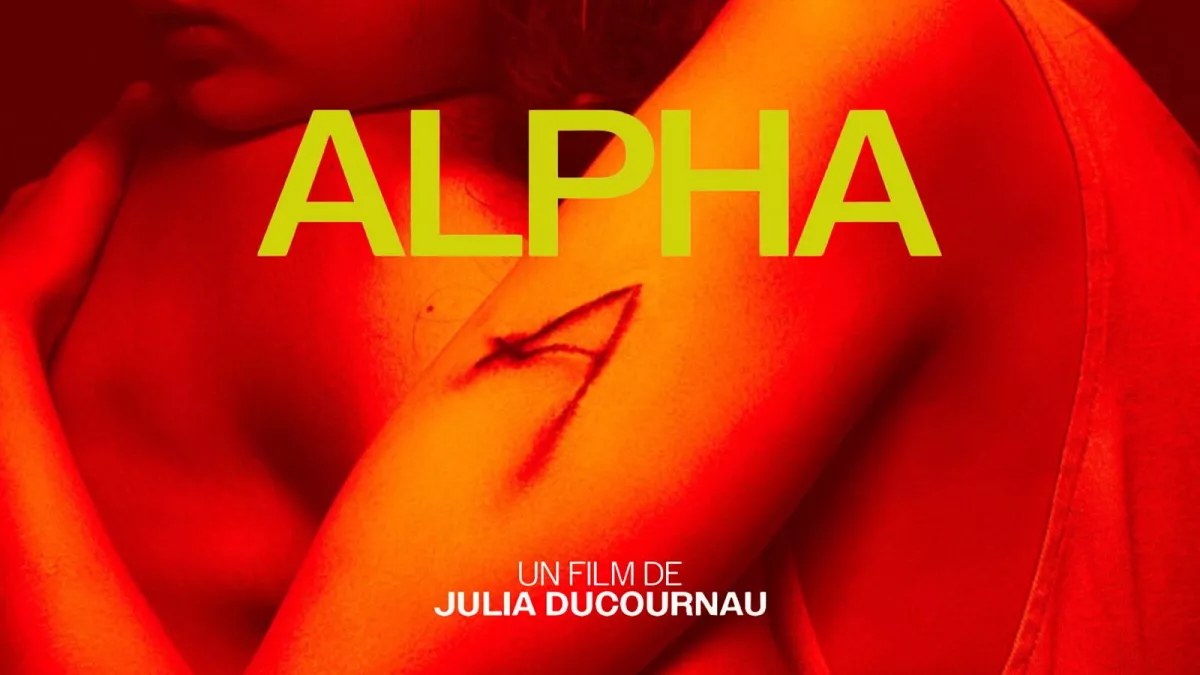

French director Julia Ducournau, celebrated for her fearless exploration of the human body and psyche, returns with Alpha — a hypnotic, unsettling, and profoundly moving film that cements her as one of the boldest voices in contemporary cinema. With the Stockholm International Film Festival already in full swing, we had the opportunity to attend the premiere of Alpha, a film that Swedish audiences can now enjoy in cinemas.

In Alpha, Ducournau once again blurs the line between the physical and the psychological, crafting a world where reality and imagination twist around one another like strands of DNA. The story unfolds through the eyes of Mélissa Boros, a remarkable 13-year-old whose tender and quietly powerful performance anchors the film. Mélissa plays a young girl standing at the threshold of adolescence, just beginning to discover herself, when a mysterious disease begins to shadow every corner of society.

Her mother, Maman, portrayed with haunting intensity by Golshifteh Farahani, is a doctor working tirelessly to fight this devastating illness — one that slowly turns its victims into marble. What begins as an epidemic of flesh becomes, in Ducournau’s hands, a meditation on the fear of transformation, mortality, and the limits of human control.

Between Flesh and Stone

Farahani’s performance as Maman is extraordinary — fragile yet fierce, driven by love and fear in equal measure. Her work in the hospital is intertwined with a growing dread that her daughter may have contracted the disease. Ducournau captures this maternal terror in scenes that oscillate between tenderness and horror, between the tactile warmth of skin and the cold perfection of stone.

Ghosts — both literal and figurative — haunt Maman’s world: the spirits of her patients, her estranged brother who spirals into addiction, and perhaps most poignantly, her own guilt. These spectres drift through the frame like echoes of a conscience, blurring the boundaries between life, memory, and delusion. As the narrative unfolds, it becomes increasingly difficult to tell what is real and what is merely a projection of the characters’ grief-stricken minds.

When Marble Becomes Mortality

The notion that those who succumb to the disease turn into marble statues gives Alpha an extraordinary visual and philosophical power. Marble — so often associated with beauty, divinity, and immortality — becomes a paradoxical symbol of death. It’s impossible not to think of Michelangelo’s David, of Greek gods and goddesses carved into perfection, of the timelessness of art and sculpture.

In Ducournau’s dystopia, this most precious of stones becomes a curse. People die transformed into objects of tragic beauty — cold, still, eternal. The film invites us to question the cost of perfection, and what it means when something associated with artistic immortality becomes the vessel of mass extinction.

By the film’s final scenes, more than a few audience members were left with tears in their eyes. Perhaps it was because Alpha doesn’t only speak of fantasy but touches something painfully real — that recent time when we, too, had to say goodbye to loved ones, when hospitals overflowed, when fear of contact separated us from each other. Just as Alpha’s classmates reject her out of fear of infection, we remember a moment in history when distance became a form of protection.

And even I, watching this film, felt a deep and personal ache — remembering the moment I had to say goodbye to my own mother during that time. In that darkness, I realised we all shared something with Alpha: the struggle between attachment and separation, between holding on and letting go.

A Mirror to Our Times

Without ever feeling literal or didactic, Alpha resonates powerfully with our collective memory of a recent era when the world itself was gripped by fear of contagion, isolation, and loss. Ducournau does not dwell on disease as a plot device but instead uses it as a mirror — reflecting how humanity reacts when faced with invisible threats, when the body becomes both a vessel of life and a potential harbinger of death.

There’s a deep sadness beneath the film’s surrealism — a recognition of how easily empathy can turn to paranoia, and how the desire to protect can transform into a desperate need to control. Ducournau captures this fragility in every frame, contrasting the organic textures of skin and breath with the smooth, unyielding surfaces of marble.

A Cinematic Labyrinth

Visually, Alpha is nothing short of mesmerising. Ducournau and her cinematographer create a dreamlike labyrinth of shifting lights, colours, and reflections — a world that feels both tactile and hallucinatory. The editing mirrors the disorientation of the characters’ inner states, with moments of stillness shattered by sudden surges of panic or surreal beauty.

In true Ducournau fashion, the film is not easily categorised. It is part body horror, part family drama, part fever dream — but above all, it is a study of love and transformation. By the film’s end, we are left questioning not only what is real within the story but also what is real within ourselves.

The Verdict

Alpha is a haunting, complex, and deeply human film. It asks uncomfortable questions about identity, mortality, and the boundaries between mind and matter. Mélissa Boros delivers a breakout performance that is both raw and luminous, while Golshifteh Farahani anchors the film with a rare emotional gravity.

Julia Ducournau’s Alpha doesn’t just tell a story — it infiltrates your senses, lingering long after the credits roll. It’s a cinematic experience that invites us to breathe, to fear, and ultimately, to feel the fragile pulse of life beneath the marble surface.